Reading Handwriting

One of the biggest challenges which is encountered in interpreting any historical document is reading handwriting. If I were Dante I would reserve a special form of eternal punishment for the bureaucrat who first decided that these documents should be filled out in longhand. That is because, despite the amount of time dedicated to teaching handwriting in school, it remains a highly idiosyncratic behaviour. Indeed it is so idiosyncratic that some people claim they can identify personality traits from your handwriting, and certainly criminologists can usually distinguish between an individual's handwriting and even a deliberate imitation of that handwriting by someone else.

To this is added the issue that we so seldom need to deal with handwriting these days. All formal correspondence, for example filling in order forms, uses block printing so it is only in personal letters that we ever see handwriting. And with the ever-increasing penetration of computers and mobile phones with text capability into our lives even that use of handwriting is fading. As with all skills the interpretation of handwriting requires regular practice, and we just don't get that practice any more. Some of the volunteers on this project are retired teachers, who have probably had more practice than most people at reading handwriting, but many of those volunteers also report problems.

Documents created in the middle of the 19th century, such as the 1842 through 1881 censuses, and many early BMDs, were written by people who came from a range of educational backgrounds, and who were therefore taught according to various standards for handwriting. In particular British, American, and French handwriting styles were distinctly different in this period. One aspect to be particularly on the watch for is the old-fashioned “sharp s” or ß. This is easy to mis-interpret as “ff” or “fs”, but should be transcribed as “ss”. The significance of the use of a “ß” instead of an ordinary “s” was that it signaled that the letter was to be pronounced as a voiceless “s” rather than the voiced “z” sound that a single letter “s” normally has in English when it appears between two vowels or after a vowel or voiced consonant at the end of a word. Note that the “sharp s” only occurs at the end of words in 19th century English. For example if you see a given name that looks like ”Agneß” or a surname that looks like “Harriß”, then transcribe it as “Agness” or “Harriss”.

Fortunately by the end of the 19th century the primary school system of teaching handwriting was well established and generally I find the 1901 census easier to read than earlier censuses, when literacy was not as general. Unfortunately the turn of the last century was the high point for hand-writing, as shortly thereafter the type-writer came into universal use in offices, and hand-writing for official purposes started its long decline to the current sad state.

The purpose of this note is to provide some useful hints on how to approach reading handwriting.

The most important rule of reading handwriting is to first familiarize yourself with the style of the individual who wrote the document. Fortunately with official documents you generally have several pages that are all written by the same individual, and that individual was to some extent recognized by the community as literate. However one must remember that the primary quality required of any census enumerator or township clerk was that they had supported the winning party in the preceding election, not that they had great handwriting. Until you are very familiar with reading 19th century handwriting do not dive straight in; first immerse yourself in the document. In particular surnames are not a good place to start, because there are so many different surnames, from so many cultures.

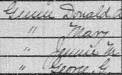

For example consider the following fragment:

At first glance the surname appears to be “Guuu” which makes no sense. However this enumerator actually has extremely good handwriting, and the given names are all perfectly obvious. It is the third line that gives the clue. The appearance of the given name “Jennie” shows that when this enumerator writes a string of “n”s they come out looking like “u”s. With this clue looking back at the surname you can see that there is a subtle difference between the second letter and the third and fourth letters, so the surname is most probably “Gunn”. Note, however, that when the enumerator writes a single “n” it has a more standard profile.

If the handwriting is particularly difficult I like to start out by creating a table of the way in which the enumerator writes capital letters. If you know what letter a name starts with you are much more likely to be able to puzzle out the rest. Also, even if you still find the remainder of the name impenetrable, when someone later comes along to use the transcription they are much more likely to be able to find their relatives if the first letter is correct. To create this table you can start with the “Sex” column. Believe it or not I have encountered censuses where it was actually difficult to distinguish between “F” and “M”! Now go to the “Marital Status” column. This is a good one because there is frequently only a subtle difference between “M” and “W”. Now go to the “Relationship” column, where you will obtain the appearance of “H” and “D”. From the birthplace column you will obtain “O” for “Ontario”, “Q” for “Quebec” (a really good letter, since people nowadays are frequently confused by its resemblance to the digit “2”), “E” from “England”, and “I” from “Ireland”. It is important to know what “I” looks like because it often resembles “J”. As a result of this potential confusion the street names in Washington, DC jump from “I Street” to “K Street”.

As you construct this table be aware that individuals will write a capital letter differently depending upon its context. In particular they will write it differently when it stands by itself as opposed to when it is the beginning of a word. The following is an example of such a table constructed from a randomly chosen census district. For this particular enumerator note how he sometimes prints the initial capitals for “H” and “S”, and switches between a round top “M” and pointed top “M”.

| A |

|

J |

, ,

|

R |

|

| B |

|

K | S |

, ,

|

|

| C |

|

L |

|

T |

|

| D |

|

M |

, ,

|

U | |

| E |

|

Mc |

|

V |

|

| F |

|

N |

|

W |

, ,

|

| G |

|

O |

|

X | |

| H |

, ,

|

P |

|

Y | |

| I |

, ,

|

Q |  |

Z |

By now you should have a feel for the originator's handwriting. Start transcribing by filling in the “Given Names” column, while staying alert for additional capital letters to fill in your table. Until you have that table complete you may continue to have problems with middle initials. Watch for names that start with “Th” or “Mc” as these combinations frequently result in shorthand abbreviations.

Only once you are comfortable with the enumerator's handwriting should you transcribe the Surname column. This is probably the single most important column in your transcription. A family historian can always go back to the images to verify that you have correctly transcribed the values for all of the other fields, but if you have not correctly transcribed the surname nobody will ever be able to find the specific record.